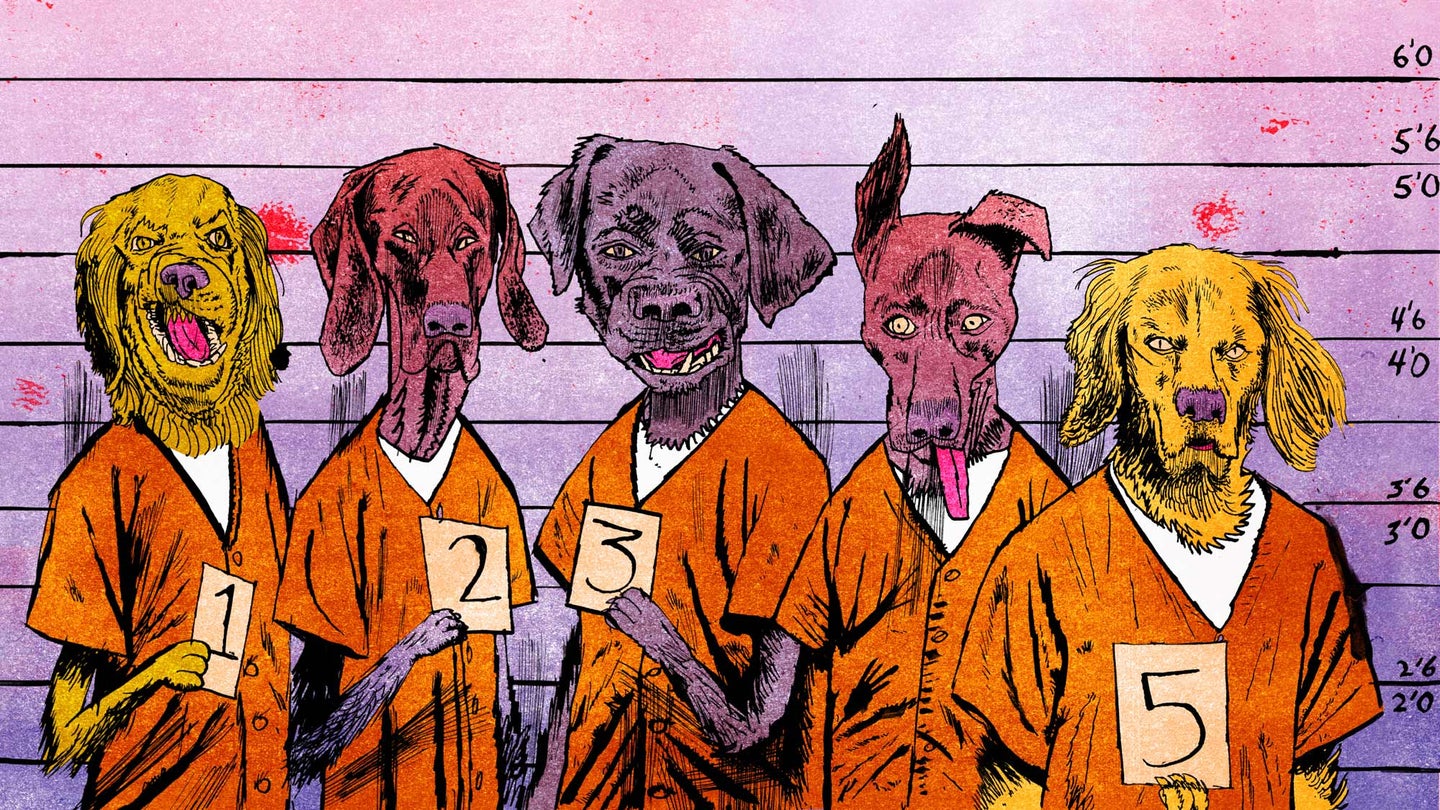

Bad Dogs! Six Stories of Canine Misconduct

Sam

In the beginning, Sam would take off at some point during almost every hunt. His departures were completely random, and not unlike those scenes in science fiction movies when a ship makes the jump to hyperspace. He’d blast off in a straight line at top speed, turn into a liver-and-white streak, and then disappear.

Sometimes he would come back after a few minutes. Other times, I’d find him on the steps of our farmhouse, waiting for me when I got home. Even after he outgrew his random bolting, Sam never accepted the fact that he couldn’t catch birds once they were airborne. His worst offense came one November afternoon when I took him on a short hunt behind the house.

The best cover was in the creekbottom, and we were almost there when I heard the whine of an engine above and behind us. I looked up to see a single-engine plane passing overhead, several hundred feet up. Sam saw it, too—and was gone.

The fields were fall-plowed, making it easy for me to track Sam’s progress until he was a tiny white speck against the black dirt. I yelled. I blew the whistle. I may have thrown my hat. Sam stopped only after a three-quarter-mile chase because he ran into the line fence. Otherwise, he would have kept after that plane until it landed.

On his way back, as I was about to start yelling at him again, Sam bumped a rooster. Realizing that the pheasant was flying right to me, I hid behind a tree. When the bird got close, I stepped out and shot it. The pheasant crashed at my feet. Sam arrived an instant later to point it dead where it lay. I picked the bird up and patted Sam on the head.

“Good dog,” I told him. What else could I say? —P.B.

Adrien Coquet / The Noun Project

Fred

The Loess Hills of western Iowa are home to some of the roughest country in the state and some of its most challenging quail hunting. We’d made a morning of it, parking in the farmyard at first light and hunting our way out and then back through the scratchy cornfields and along the tangled margins of the timber.

By the time we returned, it was getting on toward noon—“dinnertime,” as they say in that part of the world. We were invited inside to eat, and while Bob and George crated their Brittanys, Dave left Fred, his big yellow Lab, loose. He also leaned his empty Browning Superposed against the side of the house—an act so unremarkable we thought nothing of it, if we noticed it at all.

Later, on the verge of food comas, we staggered out into the sunshine and were stunned by what we saw: Fred, lying on the winter-brown lawn in a kind of trance, gnawing on the stock of Dave’s Superposed, grinding away at the round-knob grip that’s one of the hallmarks of a Belgian-made Browning. My guess is that Fred was attracted to the grip because of the salty sweat impregnated there, in the same way that porcupines are irresistibly drawn to axe handles and the grips of canoe paddles.

Dave was a blustery guy, but for once he was at a loss for words. For several seconds, he was struck dumb. Finally, he sputtered, “F-f-f-Fred….F-f-Fred….If I didn’t need you, I’d kill you!”

Fred detached from his prize and licked his lips. Sitting there with downcast eyes, knowing he’d done wrong, he wore the most defeated expression I’ve ever seen on a dog. Eventually, though, Fred was forgiven and went on to live a long, happy life. Dave got the Superposed re-stocked and, in a stroke of genius, had a lamp made from the one Fred worked over. On certain winter evenings, Dave could be caught studying Fred’s toothmarks by the lamplight and laughing out loud. —T.D.

Onan

I’ll call him Onan, but that was not his real name. He was a big black Lab, a fine retriever who would bring anything to your hand, dive into icy water without a second thought, and growl at noises in the night.

But Onan was flawed. Every so often he would hunch up at the midsection and his face would assume an unmistakable smile of pure bliss. (Don’t tell me dogs can’t smile.) I won’t describe what would happen next except to say that the result would be many thousands of microscopic Onans on the rug, or the freshly mopped linoleum floor, or the back seat of the pickup, or wherever he happened to be when passion overtook him.

Then, if his owner was present, you would hear, in an unmistakable baritone, “Onan…you…sonofabitch!” If the lady of the house discovered his transgression, a simple scream of rage sufficed.

Onan was not promiscuous. He did not have affairs. The valley where he lived did not swarm with part-Lab offspring. He was simply love’s fool.

He is gone now. He died long ago of old age, south of the border. “Warm in Mexico,” as his family said. They got another dog, a smaller breed, a good hunter. But he could not fill his predecessor’s giant pawprints.

Hopefully, Onan is in Lab Heaven, with someone to clean up after him. —D.E.P.

Minnie

It’s embarrassing, honestly. My retriever, Minnie, is a small black Lab, just under 50 pounds, but she goes nuts for Canada geese. A falling duck, a tumbling dove…she’ll zero in on anything that rains from the sky. She knows what that clipped honk of an incoming goose means, and when she hears it she starts to tremble. She’s laser-locked on the birds from the horizon to overhead, and she loves the thunderous splat of a swamp goose hitting the skinny water like nothing else.

All good, so far. She’s even steady after splashdown. It’s when she gets to the goose that things go sideways. Literally.

Minnie retrieves geese in the most awkward manner. Closing in, she takes a wide berth to make sure she’s not going to get pecked on the head—a hard lesson well learned. Then she moves in for the retrieve. But instead of the classic mid-body grab, she nabs and totes geese by a leg or a wing tip. She doesn’t even mind grabbing a webbed foot and pulling the goose through the muck behind her, like she’s some hobo dragging a bag of rags and a cooking pot or two. It looks ridiculous. When she has to cross a log or beaver dam, she’ll let go of the goose, climb on the log, and then turn around and pull the bird over the obstacle. Not classy.

I tried to break her of the habit with some of those specialized training dummies, the kind with oversized ends that force a dog to grab a target in the middle. Nothing doing.

Then one day, chest deep in the muck as she brought back a goose, I bent down to get a Minnie’s-eye-view of the swamp and realized that, with a goose in her mouth, the little dog couldn’t see a thing but a wall of feathers. Her retrieving a goose in the usual way would be like me doing the breast stroke with a zebra in my mouth. Hauling it over a beaver dam is something out of a canine American Ninja Warrior.

Panting and out of breath, she dropped goose No. 1 at my feet, and then turned around and beelined for goose No. 2. What Minnie loses in style points she more than makes up for in grit. Just bring me those geese, I figure, and if you have to haul them by the toenails, they’re still all going to taste the same. —T.E.N.

Drake and Tuff

I was standing next to Cody Jinks in a parking lot, sipping a beer in the shadow of the new North Delta duck-hunting lodge in southeast Missouri. From there, we could properly admire the decorative cypress tree towering over the concrete walkway, and the walkway itself.

Freshly finished, curing, and bright, it stood in contrast to the dark mud in the surrounding rice fields, where a group of us had hunted that morning. Only minutes earlier, the mason had taken a step back and declared the walkway perhaps his best work to date. The sound of his truck departing had scarcely faded before it was replaced by another sound not unique to the Delta South but certainly at home there. A duck hunting guide was screaming, “No, Goddammit!” at an unruly retriever.

We looked up and saw that there was not one but two retrievers, Drake and Tuff, both males and vying for dominance, with the one on top, humping furiously, winning the contest. They were bowed up and snarling and getting nearer to the wet concrete with every gyration.

I took a swig of beer and smiled, because it was as if the entire day had been scripted for my entertainment. I was there to sample and write about the hunting at the lodge. Over coffee that morning, several other guests were chattering about the massive tour bus that had pulled into the lot outside during the night. Cody Jinks himself was inside, they said, and would be hunting with us. I nodded, as if I knew who Cody Jinks was.

In the duck blind, I sat next to Jinx for an hour and a half before I realized he was a country music singer. He was mostly quiet and normal and talked about things like mallards and shotguns. But then one of the other hunters in the blind stood, as if he could no longer stand the idea of anyone being comfortable, and began singing a song, to Jinks, about duck calling.

That’s when Eric Rinehart, the lodge owner and head guide, decided we should all head back for lunch, after which someone mentioned beer, which brought a herd of us out into the parking lot, where we were now watching the two dogs hump their way toward the new walkway.

Deep down, I doubt any of us, except Eric, hoped the dogs would finish before they reached the edge of the form, and they didn’t. They humped their way right through the wet concrete and then separated on the other side, both smiling and wagging their tails as happy Labradors do, having apparently solved their differences.

It was one of the funniest things I’d ever seen, and I said as much to Jinks. He nodded, and then we both sipped our beers and watched the mason, who’d returned after a quick call from Eric, work frantically to repair the skidding Lab tracks in his walkway, perhaps his best work to date. —W.B.

Baron

Baron was the only singing dog I’ve owned. My dad, who sang quietly (and off-key) in church and hardly ever otherwise, conducted an almost nightly concert with our golden retriever. He’d sit on the floor with Baron in our family room, lay his head the dog’s chest, and sing old country western songs in an exaggerated twang. Baron would wiggle, wag his tail, and then join in with a mournful falsetto howl as Dad crooned “Walking the Floor Over You” or “Back in the Saddle Again.”

But the dog had some serious quirks, among them a fear of thunderstorms and firecrackers that bordered on the catatonic. Yet he was anything but gun-shy. I couldn’t get my Remington 1100 fully uncased before he’d start to quiver and dance with excitement, half-berserk at the prospect of finding pheasants.

In November of my senior year in high school, I was prepping for my annual Wisconsin deer hunt and decided to sight in my slug gun at a familiar farm before taking Baron out for birds there. Not wanting to make two trips, I put Baron in the back seat of Dad’s station wagon.

A cream-yellow Oldsmobile with brown faux-leather seats, it was the first new vehicle my dad had ever purchased. Raised in the Great Depression and ever fastidious, Dad was a passable mechanic who prided himself on buying used cars and nursing them along. But he folded when a dealer offered him a great buy on the brand-new Olds. We all loved the car, but to Dad it was like another child.

At the farm, I left Baron in Olds while I uncased my 1100 and grabbed my bird vest, where I’d put the box of slugs. Walking out to stake the target, I looked back to see Baron wiggling uncontrollably and pawing at the car window. But I’d only be 10 or 15 minutes. What could happen in that time? I proceeded to shoot a full box of slugs and was feeling good about the results as I walked back to fetch the dog.

When I opened the back door, Baron sprang from the Olds. As he ran circles around the wagon, barking in excitement, waiting for me to don my vest and load my gun, I slumped to my knees and surveyed the wreckage. Swaths of faux leather were peeled back in sheets, chunks of foam covered the floor, and there was a crater in the back seat I could have stuffed my dog in. Apparently, while I shot slugs, Baron decided that the most likely means of escape was to dig a hole through the seat and exit from the bottom of the vehicle. Standing there on the brink of tears, I wished the hole were big enough for me too.

Our brief hunt was less about finding pheasants than it was about delaying the ride home. Dad loved that dog, but he’d also been raised on a hardscrabble farm, where useless or belligerent animals were disposed of. He was silent during supper after I showed him the trashed interior of his beloved car, and my mind went crazy imagining his plans for Baron. It was my turn to help Mom with cleanup, and as we started tidying the kitchen, Dad called for Baron and disappeared down the hall. I looked at my mom for some clue, but she remained stone-faced as she scrubbed dishes and handed them to me for drying.

It seemed like an eternity until I received a clue to Baron’s fate. Finally, between clanking plates and clattering silverware, I heard a faint, tremulous howl. When I glanced at mom, she was grinning, and I tossed my towel down, raced to the family room, and saw dad’s head on the chest of my retriever, who wagged his tail and howled along as Dad warbled “Why, Oh Why, Did I Ever Leave Wyoming.” —S.B.

Read more F&S+ stories.

The post Bad Dogs! Six Stories of Canine Misconduct appeared first on Field & Stream.

Articles may contain affiliate links which enable us to share in the revenue of any purchases made.